Australia in the 1950's

Fourof the children born to Pat and Norah Coleman of Cahermaculick, Shrule, Co Mayo, Ireland settled in Sydney in the 1950's and 60's:

Michael (Mick) (1933) in 1957 after two years in North Queensland; Martin (1937) in 1958 and Delia (1942) and Margaret (1945) in 1966.

1st Generation Australian

Michael (Mick) Coleman - Sydney 1957

After years of deprivation and suffering through the Great Depression and World War II, the 1950s were prosperous years for Australians. Employment was high and the rapid advance in Technology after the war soon transformed the lives of many Australians.

Between 1945 and 1965 two million immigrants arrived in Australia. The Australian Government had decided to open up the nation because it believed there was an urgent need to ‘populate or perish’ after the Second World War. Among the new immigrants were the first non-British migrants allowed by the Australian Government. This massive influx of people eventually transformed Australian society. Some families were already able to afford a refrigerator, a freezer, or even a dishwasher. A considerable time-saver for housewives was the purchase of smaller appliances, such as blenders or toasters.

The rapid growth of suburbs in the 1950s was largely due to economic growth, improvements in transportation, and Federal policies that made suburban home ownership more accessible.

Steam engines and the Suez shortcut in the late 19th and early 20th centuries reduced the journey from Europe to about 40 days. In the 1950s, the liners were able to make the journey in about 25 days.

From 1947 the government organised the immigration of displaced persons from Europe. A total of 170,000 such migrants had arrived by 1953. Many lived in hostels until they were sent to regional areas where they were required to work for two years. Shortly afterwards, assisted immigration was offered to Europeans willing to work, particularly those with family contacts in Australia. The ‘populate or perish’ policy enabled large numbers of Greeks and Italians to immigrate. The Greek born population in Australia doubled between 1952 and 1954, and by 1961 it reached 77,333. The 201,428 Italians who arrived between June 1949 and July 1959, made up 16% of all immigrants. In 1947 there were 33,600 Italian born residents in Australia and by 1961 there were 228,300.

In 1957, Australia volunteered to accept 14,000 Hungarians affected by the invasion of their country by the USSR. Also that year non-European migrants with 15 years residence in Australia were declared eligible to become Australian citizens. The following year the Immigration Act was revised with no reference to race or the long-standing dictation test that had been used to discriminate against certain nationalities; its removal marked the beginning of the end of the White Australian Policy. Further changes were introduced in 1959 allowing resident Australian citizens to sponsor their non-European spouses and any non-married children, who could then apply for citizenship.

Most Australians living in Sydney and other major Australian cities in the 50s knew very little about the Aboriginal people. While there was a general awareness of the skills of Aboriginal stockmen and trackers in outback Australia, very little was known about the lives of Aboriginal people. Most lived on cattle stations or reserves run by the government or church organisations and a few still lived traditional lives in very remote areas. None of them enjoyed the rights or benefits afforded to Australian citizens.

One of the major threats to health in the 1950s was polio. The Salk vaccine was introduced in Australia in 1956 and this proved a turning point in treatment.

In the 1950s assistance was extended to families and pensioners. Child endowment had been introduced in 1941, and in 1950 it was extended to cover the first child. The Pensioner Medical Service was established in 1951 to provide free medical treatment to pensioners with payment made directly to doctors and hospitals. Pensioners became eligible for rent assistance in 1958.

Australians continued to work a 40 hour week during the fifties, the female wage rate increased from 54% to 75% of the male wage in 1950, and New South Wales led the other states in the introduction of long service leave in 1952.

About one month before his nineteenth birthday, My brother, Mick Coleman, settled in Birmingham England in 1954. He worked there for less than a year before sailing to Australia aboard the 'New Australia' in June 1955 under the Assisted Migrant Scheme. He was born in 1935 as the second son and child of Pat and Norah Coleman, a farming family, who lived in Cahermaculick, Shrule, Co. Mayo, Ireland.

Norah & Pat Coleman 1933

Pat & Norah Coleman in Sydney in 1977 with

their children Mick, Martin, Delia & Margaret

Aboard the ship, Mick met another Irishman, John Peters, from Northern Ireland. John was an experienced diamond driller who had worked in Africa and was on his way to join Thiess Brothers in Mary Kathleen in North West Queensland at Australia’s first uranium mine. I believe Mick was meant to have stayed in Sydney although I couldn’t see the Government objecting to his opting for Mary Kathleen on the other side of the never never.

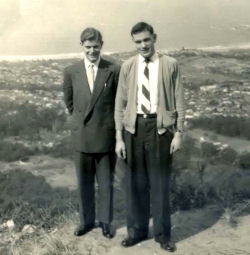

Mick (R) & Martin Coleman 1958 at Bulli Tops Mick (R) & Martin Coleman 1958 at Bulli Tops |

So on their second day in Sydney, they took the train for the long trip to Brisbane. On arrival, they reported to Immigration to claim back their entitlement of five pounds, 50% of the cost of the passage out, a fair sum back then, before calling at the headquarters of Thiess Brothers where they were warmly welcomed by Pat, Cecil and Les, three of the seven brothers involved in the company. They were provided with lunch and accommodation and given two days off to take in the sights of Brisbane before heading north in the company plane to Townsville where they stayed for the weekend before boarding the silver ‘Overlander’ for Cloncurry located in the Gulf Savannah region of the state.

Today, Cloncurry is still an important mining town with a population of 2,758. Back in 1861, John McKinlay, leading a search for Burke and Wills, reported traces of copper in the area. Some six years later, pastoralist Ernest Henry discovered the first copper lodes. During World War 1, Cloncurry was the centre of a copper boom and the largest source of mineral in Australia. But shortly after the war a pastoral industry took its place when copper prices slumped. Qantas was conceived there and the original hangar can still be seen at the airport. The town also became the first base for the famous Royal Flying Doctor Service in 1928 which was founded by Irishman John Flynn, and later still it became the training centre for the state’s police force.

When Mick and John arrived there in 1955, its population was a mere few hundred. It boasted, however, five hotels to cater for the visiting bushmen and miners escaping the blistering sands and the scorching blinding sun pounding away hour after hour, day after day, week after week until the only relief was escape. The respite was welcome and indeed essential to one’s sanity. As severe as it was, this wasn’t the only predicament that miners like Mick and John faced. On arrival in Cloncurry, they were taken by jeep to the uranium mine at Mary Kathleen, a centre located about 65 kilometres from Cloncurry in the direction of Mount Isa and now long abandoned.

The incessant heat and scourging light, the repetitive work, the dust and tormenting isolation, all took their toll in one form or another. Mick and John Peters worked as a team out in the open and up to a few miles from the mine drilling to locate the much valued uranium. Being exposed to the elements had its advantages over the conditions in the dusty mines where dry drilling was the order of the day.

Though paid by the foot drilled, how much Mick and John actually collected at the end of the week was entirely up to them as the number of bores recorded was never checked. It meant that they were collecting on average up to ten times the weekly wage. There was no scarcity of diamond drills to replace those left behind stuck in the bores and those not stuck in the bores. The American bosses in charge were more than willing to supply all the drills requested though some of them were making their way into the hands of other mining companies.

A high percentage of those working in and around the mines and towns were in fact Irish and the scenes they regularly created when they hit town didn’t quite endear them to the local constabulary. Though company policy was a bottle of beer per person a day, alcohol was a problem as many of the men sneaked out of camp during the night and were in Cloncurry an hour later. There was no scarcity of vehicles. Mick found the aborigines who worked there to be reliable, intelligent, very friendly and hard-working. Pat Thiess was in charge of operations and come Friday it was not unusual for him to down tools for the weekend and head for town with the boys. Mick has many pleasant memories of their taking him to Mary Kathleen for his 21st Birthday. The mine had its own preferred hotel in Cloncurry, the “Serwyn” that among other things provided good entertainment and accommodation.

When John Peters did not return as planned after a weekend in Cloncurry, Pat Thiess dispatched Mick to locate his friend and bring him back. Having sought him in vain in the usual places, he turned to the publican’s wife at the “Serwyn” who was well respected by the townsfolk. The local police didn’t have the best of reputations for tolerance, and so if he was to get anywhere with them he needed the help of someone like her. His hunch was right. The police had picked up John and sent him to the Goodna Mental Asylum in Brisbane when all he really needed was time to dry out somewhere away from the alcohol. Mick was very concerned for his friend and immediately took a plane to Brisbane. He decided to first visit Immigration and to explain the story to them in the hope that they might be able to help. As it worked out, they were very helpful. Mick located John and signed him out. He was looking and feeling remarkably well but had no hope of getting out of that place on his own. After spending a couple of days sorting things out and buying some new clothes, they returned to Mary Kathleen. A short time later, Mick and John’s other friends persuaded him to visit a doctor in Cloncurry who advised John to leave North West Queensland for a cooler place such as Tasmania. This and the fact that he was worried about what the police would do to him should they see him in town again particularly after a drinking session got him thinking about moving on. Having set his mind on New Zealand, he headed for Sydney accompanied by Mick who was to help him organize his trip across the Tasman. After seeing him off, Mick returned to Mary Kathleen but was unable to settle back into the routine of drilling. For the next few months after a short period of training, he operated one of the mine’s large bulldozers. Most of the heavy equipment used by the mining authorities was American left behind after the War. During this time, Mick heard from a person from home, Bill McDonagh, who had settled in Sydney. Bill had worked in London with me, and had promised to contact Mick once he got to Sydney. Prompted by this, Mick decided a few months later to pack his bags and head for the big smoke towards the end of 1957 where he lived for the rest of his life mainly as a hotel owner and proprietor.

2nd Generation

Mick Coleman (1935) married Mary Brooks (1938) on 18th August, 1964

and they are seen here with Daughters Catherine (1965), Noreen (1967),

& Bernadette (1968) and Sons Michael (1971 & John (1972)

3rd Generation

|

Roisin (1999), Michael (1997), & Patrick (1995) |

Bernadette's Family Aiden (2003) & Chloe (2004) |

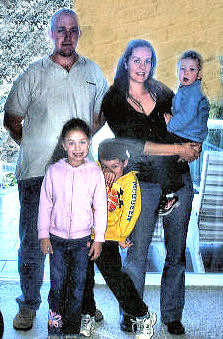

Jessica (2001), Michael (2001) & Joshua (2005) Michael Coleman (1971) married Monique Atkins (1973) on 8th March, 1997 and they are here with Jessica, Michael & Joshua - 2007 |

John's Family Liam (2000), Jack (2002) & Alana (2005) |

Back to Family Centres - Forward to Sydney Pag 2 (Martin Coleman)

Clan Coleman

Clan Coleman