The Coleman Ancestral Home

|

The boreen through the village

|

Turloughmore Village

1997 Photos by Martin and Patricia Coleman |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

During the Clan Coleman Reunion in 2004 some members took time out to visit the village of Turloughmore on 7 August. The picture on the left shows Martin Coleman, Kevin Meehan, Mary and Mick Coleman, Mary Meehan, Linda Downie, Barbara and Patrick Coleman, Martha Caluori, Jack Downie and Linda Timms, Patricia Coleman and Roisin Naughton. |

|

|

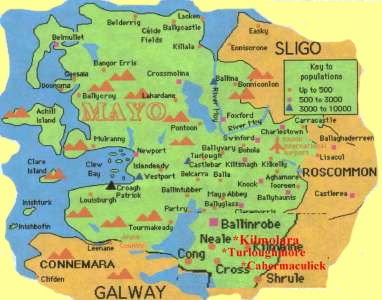

The Townland of Caherheamush (Turloughmore) in the Parish of Kilmolara

It was here that our Coleman ancestors had lived for centuries until my Grandparents and their Family relocated to Cahermaculick in 1917 |

|

|

The townland of Caherheamush is in Irish Cathair Shéamuis which means 'James's Stone Fort'. It was referred to as Caher James in an Inquisition in the time of Elizabeth 1 and as Caherenuish in the Down Survey Map. It is located in the centre of the civil parish of Kilmolara and contains 134 acres, 1 rood and 17 perches of land. In the 18th and 19th centuries it was part, and one of the poorest parts, of the property of the Browne family of The Neale the heads of which held the title Baron Kilmaine. The soil is light and rocky and produced poor tillage crops. The area in which Caherhemush is located is referred to locally as Turloughmore because of the flooding which occurs there in the winter months. Indeed the townland name is rarely used save in legal documents. The tenants were all Roman Catholics in 1838.(1)

|

|

1.

|

Ordnance Survey Field Name Book, compiled 1838, unpublished. |

|

|

| From Bald's Map of Mayo compiled circa 1812 showing the village of Turloughmore with a cluster of fourteen houses |

|

| Ordinance Survey Field Map 1838 |

|

In 1838 the farm sizes in Caherhemush varied from 1½ to 8 acres which would suggest that there were at least 16 houses in the townland and perhaps several more. In 1841 the population of Caherhemush was 87 persons in 16 houses. By 1851 the population stood at 72 persons in 13 houses (2). This suggests that three households died out or emigrated during the period of the Great Famine but also suggests that the number of houses had been reducing in the period 1838 to 1841.

|

|

2.

|

Census of Ireland, Part 1, Area, Population and Number of Houses |

|

From the Coleman genealogy we are aware that the Colemans were involved in flax growing and linen production in the 1790s. Flax growing provided sufficient employment and income in the period 1770 to 1815 to allow families to exist on small holdings despite the systematic ruthlessness with which Ireland's trade and industries were being wiped out by England. "Only the coarsest kinds of undyed Irish linen were admitted to the British Colonies. Checked, striped and dyed Irish linens were excluded. Besides, no Colonial goods could be bought in return. And Irish linens of every kind were forbidden to be exported to all other countries with the exception of Britain" (Seumas MacManus, p.489). There a thirty per cent duty was imposed on it while a bounty was granted to the British linen manufacturers on all linen exports! So England destroyed this industry as it had earlier destroyed the very successful Irish ship-building and wollen trade, not by competition but by legislation, and later the hempen, beef, lamb, cotton, glass, tea and tobacco trades.* Consequently, the population who resided on small holdings were forced to subsist more and more on the produce of their holdings and on whatever occasional employment they could find. Since the potato supplied the greatest volume of food per acre it became the stable food. Oats, the most lucrative cash crop, became the main source of income and went mainly towards rent payments. Season migration to the north of England for agricultural employment also became a feature of life for small holders and their older sons. |

| * Click HERE for a more detailed description by MacManus and HERE for The Neale and the land problem |

|

The failure of the potato crop in the years 1845 to 1850 - the Great famine, an Gorta Mor - led to large-scale emigration. Farm holdings gradually grew in size in the years after the Famine. From the 1830s the average age at marriage increased dramatically. Consequently, family size dropped and the subdivision of holdings ceased. In the aftermath of the Famine more land was given over to grazing. The lot of the Irish did not really improve, and a number of very difficult years as well as the prospect of another major famine in the late 1870s led to a period called the "Land War". The success of this movement meant that the landlords were losing their power and grip on the land. Periodically though evictions continued to be carried out despite the protests and whole families, orphans and widows were forced into the Workhouse in Ballinrobe. This charnel-house of the Great famine survived still to inflict utter pain and mental torture, separating families on entry and thereafter subjecting them to hard labour and often premature death. |

|

Spurred on by the Land League movement, tenants were more than anxious to own their own land and in the spirit of Brehan Law, that for so long was part of their deeper memory, they insisted on that right. Land acts were passed poviding for a degree of tenant land purchase. The Irish were at last emerging from centuries of coercion and oppression. Co-ops were set up that became the focal point of the community. Those changes as well as the founding of the GAA or Gaelic Athletic Association and the Gaelic League breathed new life into rural Ireland as up until the late 1890's the Irish were also barred on social grounds from competing in sports and games. The Gaelic League was founded to halt the decline of the Irish language and promote a revival of Irish culture. The literary revival that followed, based on a fast growing awareness of Irish nationality and inspired by Ireland's past, led to a Celtic renaissance that revitalised the Irish psyche. |

|

The centuries of coercion, oppression and famine which had caused so much misery and pain had made poverty endemic and the cure proved ever so elusive. By 1903 when my father was born, life was improving, albeit ever so slowly, for the people of Mayo and elsewhere . By today's standards it was indeed a very exacting and meagre existence with few comforts. Homes were cold and draughty with no indoor plumbing and little furniture. Meals were cooked in pots and pans over open fires. Most farm work was done by hand with the aid of the spade and the fork, the sickle,the scythe and the rake. The donkey and the horse were the beasts of burden. When it came to farm work, the horse was the farmer's most prized possession as it was used to pull the plough, the harrow and the cart. |

Clan Coleman

Clan Coleman