Genealogy Menu

In this page you will find a short statement that gives you a general view of our family history. It comprises a summary of headings and short paragraphs organised to give you an outline of the whole story. For those of you not interested in history, it will stand as enough for now at least, but for all others it will present a meagre outline of much more interesting things to come in the pages ahead. On a few occasions when describing to others how our family history will also include a number of articles on important events in Irish history, I have been reminded that 'such things are best forgotten' or that 'we must put those things behind us and not dwell on the past'. My problem with those types of comments is that they are invariably used to cover up one's own ignorance of history or are used as an excuse by others who don't want us to know about such things for whatever reason.

I feel it's reasonable to assert that if you want to really understand the present, you must try to understand the past. What has happened in the past has determined in no insignificant way what and where we are today. By way of analogy, to clearly understand the workings of the modern motor, you need to embrace the history and science of its development. In other words, you need to acquaint yourself with the language and thought processes involved in its evolution. The same thinking applies to all other situations whether cultural, historical, religious or scientific. How can you be expected, for example, to understand your religion without knowing the history of its development?

Celtic Ireland was divided into a number of small kingdoms or tuatha (TOO-ha), with the number gradually increasing to about one hundred and fifty by the turn of the seventh century AD, and each ruled by a king or rí (REE). A number of these rulers were also over-kings, receiving tribute from neighbouring kings. There were also kings of provinces, and a high king, or ard-rí of all Ireland. The two pivotal institutions of the time were the fine (FEEN-eh) or joint-family which was the social unit, and the tuath (TOO-eh) or petty kingdom- the political unit. The fine included all relations in the male line of descent for five generations and in it was vested the ultimate ownership of family land, fintiu (FEEN-chew).

Initially Ireland was divided into the so-called 'five fifths of Ireland'. These corresponded to the present provinces of Ulster, Connacht, Munster and Leinster, except that north Leinster formed the Middle Kingdoms or the ancient Irish territories of Mide (Mee-de) and Brega or Breagh (Breh), which roughly equate to the modern counties of Meath and Westmeath.

There was no system of primogeniture. Land was shared equally between brothers but the head of the senior line of descendants was the cenn fine (CAN), who represented the family.

In royal families, each king was elected from a small group of people, known as the geilfhine (GAYL-fee-ne) or derbfine (also deirbfhine) as often called, and comprising the male descendants of a common great-grandfather, four generations in all. A tánaiste rí (TAWN-ish-teh) or heir-apparent was usually elected during the king's lifetime.

The áes dána (AWS DAW-na), the 'men of art', constituted the most important element of early Irish society and comprised the learned classes, the poets, the brehons, the historians and genealogists as well as the musicians, and the skilled craftsmen.

The brehons (BREH-huns) were professional lawyers, who had drawn up a very elaborate scheme of the different degrees of relationships, and when disputes arose, it was to them that people turned as arbitrators, for there was no public enforcement of law.

The filidh (FEE-lee) were more than poets. In addition to composing and reciting poetry they were custodians of the history, mythology and genealogy of the Celts.

(i). While the information here is derived from a number of sources, the main two are a brilliant book entitled "Early Irish Contract Law" by Dr Neil

McLeod and "The Course of Irish History" edited by TW Moody and FX Martin.

|

1.

|

This then was the political and social structure when Eochaidh Muigh Meadhoin (OH-he Muee -Moyvone) became Ard-Rí, the 124th Monarch of Ireland, in 357 AD. He had five sons, Brian, Fiachra, Oliol, Fergus and Niall. From his sons sprang the powerful Uí Néill (EE-NALE), Uí Bríuín (EE-BREEN), and Uí Fiachrach (FEE-kra) line of kings of Ireland, Ulster, Midhe, and Connacht for the next 700 years. From Fiachra and Brian were descended the two most dominant dynasties of Connacht, the Uí (EE) Fiachrach and Uí Bríuín Dynasties. Fiachra's descendants gave their name to Tír-Fiachra (Cheer-FEE-krah) in north east Connacht, known today as Tireragh (CHEER-rah) in County Sligo but also included back then parts of north-east County Mayo. |

|

2.

|

Niall was himself a powerful prince of the Connachta and became the 126th Monarch of Ireland in 378 AD. Nine tuatha around the northern capital of Emhain Macha (EV-n MOK-ha) put themselves under the protection of Niall and formed a federation called the Airgialla (eerGEE-lah) -'the hostage-givers' - from whom Niall got the epiteth of Noígiallach (Nine Hostages) - Niall of the Nine Hostages. His descendants took the dynastic name of Uí Néill. Two of his sons, Eoghan (Owen) and Conall conquered north-west Ulster and founded there the great Northern Uí Néill Dynasty with its capital at Aileach, and the others ruled in Mide and Brega as the equally powerful Southern Uí Néill Dynasty. Almost without interruption Niall's descendants were considered the high kings of Ireland for 600 years with the position alternating between the Northern and Southern Uí Néill Dynasties. |

|

3.

|

While Fiachra's son, Dathi (DAH-hee), succeeded Niall of the Nine Hostages in 405 as Ard-Rí (High King), It was Niall's son, Laeghaire (Lah-HEE-reh), as the 128 Monarch of Ireland who received St. Patrick at Tara in 432, an event that led to the conversion of Ireland to Christianity. He chose Ard Macha (Armagh) close to Emhain Macha, the great hill fort once occupied by the Gaelic kings of Ulster, as the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. As the gospel spread, more and more people wanted to dedicate their lives to God. In this rural society there were no great towns or cities where they could join together in prayer and contemplation, and so monasteries quickly came into existence. |

|

4.

|

The collapse of the Roman Empire meant that communication with the mother church was impaired, and the Celtic Church in Ireland developed its own separate character and rites. While a number of monasteries existed before then, the first Irish monastery to become famous was founded by St Enda on the Aran Islands at the end of the fifth century. St Finnian founded Clonard early in the sixth century. He became known as the 'teacher of the saints of Ireland', for twelve of his pupils, often referred to as the 'twelve apostles of Ireland', founded a number of important monasteries. They included ones by St Columcille, or St Columba the name under which he usually appears in accounts written outside Ireland, at Derry, Durrow, Kells and at 38 other places, all by the time he had reached the age of forty-one. In fact by the time of Columcille's death in May of 597, sixty monastic communities had been founded in his name in Scotland alone. |

|

5.

|

St Columcille (Columba) was the greatest Irish figure after St Patrick. He was born and baptised Crimthann (Fox) at Gartan, County Donegal, in 521. He was prince of Clan Conaill of Tir-Conaill and direct descendant of Niall of the Nine Hostages whose son Conall had founded this dynasty. It was during his days of study under St. Finian of Moville (Co. Down) that he was given the monastic nickname of Columcille or Dove of the Church, Columba being the Latin for dove, and Cille the Irish for Church. |

|

6.

|

As Irish monasteries had quickly attracted thousands of foreign students, the Irish monastic tradition began to spread beyond Ireland and, as the learned Thomas Cahill puts it in 'How the Irish Saved Civilisation', "Columcille's reputation spread like wildfire". The other Columba, Columbanus, following in the steps of the great Columcille, left the monastic community of Bangor for the continent in 590, just seven years before Columcille's death. |

|

7.

|

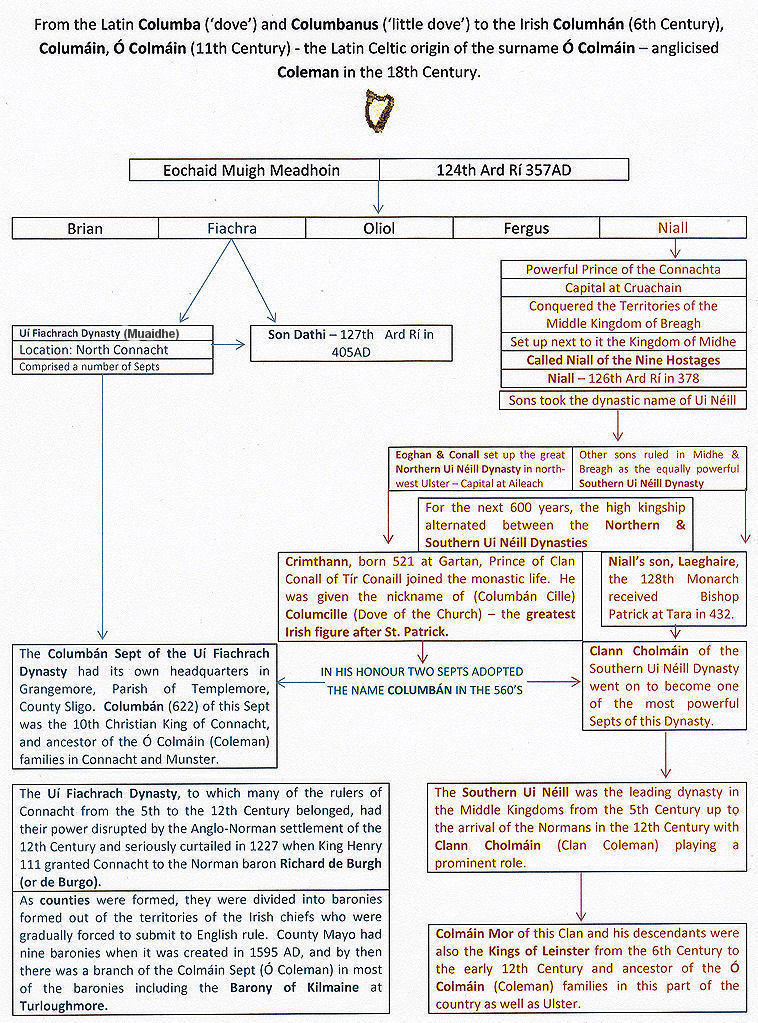

The fact that there are thousands of references in ancient manuscripts and books with over a thousand in the "Annals of the Four Masters" alone to monks, abbots, bishops, clans and kings with the name Columhán, Columáin, Colmáin (Kol-mawn) - the Irish for the latin Columba (Dove) and Columbanus (little dove) - and also that there are well over a hundred Irish saints of this name attest to the popularity of the two Columbas. While this symbol of peace was a very popular choice as a religious name among those turning to the gentler ways of the church from the earlier Irish warrior society, it was also adopted as a clan name by cousins of Columcille in both the Southern Uí Néill (Middle Kingdoms) and Uí Fiachrach (Connacht) Dynasties. |

|

8.

|

Uí Fiachrach Dynasty

Connacht |

Southern Uí Néill Dynasty

Mide and Brega |

|

|

9.

|

Uí Fiachrach had two main branches, one in the north of that province, the Uí Fiachrach Mauidhe, and the other in the south, the Uí Fiachrach Aidne which also dominated much of north Munster in the 7th century. |

The Southern Uí Néill were the leading dynasties in the Middle Kingdoms from the 5th century up to the arrivals of the Normans in the 12th century with Clann Cholmáin (Clan Coleman) playing a prominent role. |

| 10. |

The Colmáin sept belonged to the Uí Fiachrach Mauidhe branch and were chiefs or princes of Tireragh until the arrival of the Anglo-Norman families in this area in the early thirteenth century. The sept had its ancient headquarters in the townland of Grangemore, parish of Templeboy, County Sligo. Columhán of this sept was the 10th Christian King of Connacht, and ancestor of the Colmáin (Coleman) families. He was slain in 622 by Rogallach mac Uatach of the Uí Briuin at the battle of Cenn Bugo (Cambo, Co. Roscommon).

|

|

Uí Fiachrach and Uí Bríuín Dynasties |

| 11. |

The Uí Fiachrach and Uí Bríuín, to which all the rulers of Connacht from the 5th to the 12th centuries belonged, had their power disrupted by the Anglo-Norman settlement of the mid 12th century and seriously curtailed in 1227 when the English king Henry III granted Connacht to the Norman baron Richard de Burgh (or de Burgo). |

|

12. |

As counties were formed, they were divided into baronies formed out of the territories of the Irish chiefs who were gradually forced to submit to English rule. County Mayo had nine baronies when it was created and named in 1595 AD. and by then there was a branch of the Colmáin sept (Ó Colmáin) in most of its baronies including the barony of Kilmaine which had been formed from the ancient territories of Conmaicne Quiltola. |

| 13. |

My Great Great Great Grandfather, |

| 14. | My Great Great Grandfather, *PATRICK COLEMAN (1775 - 1860) held a house, out-office and approx. 161/2 acres of land in1856(1). He married and had issue: |

| I. | My Great Grandfather, *JOHN COLEMAN (born 1809, died 15 March 1892 aged 83 years)(2) married Catherine Heskin (born 1831, alive 1901 aged 70 years)(3) and had issue: |

| A. | Winifred Coleman married Martin Hughes, (born circa 1857), a farmer of Bullaun, son of Patrick Hughes, a farmer, in The Neale RC church on 26 July 1895 (witnesses: Redmond Walsh and Bridget Coleman).(4) They had issue: |

| i | Mary Hughes, born 9 February 1897,(5) baptised 9 March 1897 (sponsors: Michael Hughes and Bridget Coleman).(6) She resided with her grandmother in 1901.(7) | |

| ii | Patrick Hughes, baptised 25 April 1899 (sponsors: John Coleman and Bridget Farragher).(8) | |

| iii | Sabina Hughes, baptised 18 April 1903 (sponsors: Peter Hughes and Bridget Conry).(9) | |

| iv | Bridget Hughes, baptised 23 October 1904 (sponsors: Thomas Reilly and Mrs. Farragher).(10) |

| B. | My Grandfather, *JOHN COLEMAN (born 1859, died 14 January 1932 in Cahermaculick, Shrule) resided with his mother in 1901 age understated as "30" years.(11) He married 1901 Mary Davoren (died 22 January 1932) of Inishmacatreer in St. Mary's Church, Claran, Co. Galway on 25 May 1901 and had issue: |

| i | *MARY COLEMAN , born 8 June 1902, baptised 10 June 1902 (sponsors: James Davoren and Margaret Holleran).(12) |

|

|

My Father

|

ii | *PATRICK JOSEPH COLEMAN, born 25 August 1903, baptised 29 August 1903 (sponsors: James Davoren and Margaret Holleran).(13) |

| iii | Bridget Coleman, born 30 January 1905, baptised 31 January 1905 (sponsors: John Davoren and Margaret Holleran).(14) |

|

| iv | *JOHN JOSEPH COLEMAN, baptised 25 February 1906 (sponsors: James Davoren and Margaret Halloran).(15) |

|

| v | *JAMES JOSEPH COLEMAN, born 13 February 1909, baptised 14 February 1909 (sponsors: James Davoren and Margaret Halloran).(16) |

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------- |

||

| C. | Bridget Coleman, baptised 6 January 1873 (sponsors: Patrick Coleman and Bridget Heskin). She married Patrick Vahey of Mucrossaun, son of Patrick Vahey and Ellen Rochford on 10 March 1901 (witnesses: Michael Heskin and Margaret Heskin).(17) They resided in Mucrossaun and had-issue: |

| i | Bridget Vahey, born 13 January 1902, baptised 14 January 1902 (sponsors: John Coleman and Catherine Casey).(18) |

|

| ii | Mary Vahey, born 21 March 1903, baptised 22 March 1903 (sponsors: John Heskin and Margaret Heskin).(19) |

|

| iii | Ellen Vahey, baptised 7 April 1904 (sponsors: Patrick Farragher and Mary Farragher).(20) |

|

| iv | Michael Vahey, baptised 13 December 1906 (sponsors: Martin Casey and Bridget Malley).(21) |

|

| v | Catherine Vahey, born 30 December 1907, baptised 31December 1907 (sponsors: Patrick Vahey and Bridget vahey).(22) |

|

| vi |

Catherine Anne Vahey, baptised 29 September 1909 |

|

| vii | John Vahey, baptised 26 January 1911 (sponsors: James Malley and Bridget Coleman). He married 20 January 19- to Anne Feerick of Kilconly.(24) |

|

| viii | Anthony Vahey, baptised 8 April 1912 (sponsors: Michael Farragher and Bridget Hoban).(25) |

|

| ix | Patrick Vahey, baptised 11 April 1915 (sponsors: Patrick Farragher and E.Malley).(26) |

| D. | Patrick Coleman, a labourer, born circa 1855/1858, died unmarried on 24 January / 20 February 1891 aged 33/36 years.(27) |

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Group 14. 1. B. i. ii. iii. iv. v. above are developed further to show all branches to the present. For your branch and family tree go to your place or country of residence in the Index , click on it to open it and then click on your name. |

Forward to The Beginning

Genealogy Menu

Cahermaculick Today and Yesterday

Often I think of where I was born and the family home in the townland of Cahermaculick in the parish of Kilmaine, County Mayo, Ireland*. Whenever I return there, despite my willingness to acknowledge the very significant improvements in the lifestyle of its people, I privately bemoan the demise of tillage in favour of dry stock, where all you see are cattle or sheep in green field after green field with the word ‘herding' being freely used to convey its modern connotations of vets, artificial insemination, motorised buggies and an array of tractors as against those of the past when simple caring on foot was all it took. Today, it's so uncomfortable to walk across the fields to childhood haunts because of the unevenness, the hoof holes and the mud caused by herds of cows and other stock. Gone are many of the woodlands and the hedges of blackthorn and hawthorn that once separated the meadows, the lakes and ponds, the fields of oats and barley, wheat and potatoes and all those drills of carrots, parsnips, cabbages, and onions. Gone through organised drainage is the lake as well as the unending lines of wild daffodils that stood so colourfully and majestically along its northern foreshores. As you came over the small hill between our home and the lake, this large expanse of wild daffodils came into view as a beautiful golden carpet. The contrast was breath-taking! I was first introduced to Wordsworth's Daffodils when I was away in college in Cork as a young teenager. This poem nearly said it all for me.

* Its postal address is Cahermaculick, Shrule, Co. Mayo.

1 wander'd lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden daffodils,

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the Milky Way,

They stretch'd in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Qutdid the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay

In such a jocund company!

I gazed-and gazed-but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought;

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Missing, however, was our wandering through the thousands of wild daffodils that were taller than we in order to observe the many birds' nests they concealed. The flights past our home of large flocks of birds, including wild ducks, geese and swans on their way to and from the lake were daily occurrences.

The local community, like all other communities throughout Ireland, has so many stories that will never make the history books. Its history, as well as that of the Irish nation, and its rich folklore has always fascinated me, despite my living on the other side of the world, because through them I am able to link with my roots and enjoy that feeling of family continuity which is so important to me.

There is, however, no way that our family's way of life when I was a child will ever be known to you unless I provide a few windows through which you can see for yourself a world that was so different from your own. Ours was a farming neighbourhood with its own style of mixed farming that was quite labour intensive and involved everyone in the household. You bred and reared your own fowl and stock and when the time was right sold most of them at the local fairs. Hens, ducks, geese and turkeys roamed the yards alongside every house right across the countryside. All the tiny chickens, ducklings and goslings were forever a great source of joy and fascination to us as children. We didn't have to read about them in books. We were there for their hatching and their breaking through the shells, captivated by their taking that first step or beakful of milk or meal. The young piglets, or bonhams (from the Irish ‘banbh') as they were called, were equally captivating as were the young lambs in springtime as they played and cavorted their way around their feeding mothers.

Whenever I visit a fruit shop or the nicely arranged fruit shelves in super markets and shopping centres where in many instances it all only looks so fresh, I recall the beautiful orchards in the village of my childhood and all that very fresh and crunchy fruit. Alongside just about every home were a well-kept orchard and a vegetable garden the likes I have not seen since in all my visits to Ireland. It is so hard today to imagine their ever being there. The people were very proud of their orchards and gardens, and indeed very protective of them, particularly the orchards that were often the target of well planned incursions by the local youth on their way home from school. This rural structure of small farms of between thirty and forty acres coincided with the removal of the English and their semi feudal system from most of Ireland during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Prior to this development, most of the Irish people were huddled into small villages where the average family was forced to exist on between one to five acres of land rented from the local landlord. This land was usually the least arable in the region. Towards the end of the 19th Century some tenants with good rent-paying records were allowed to rent a few extra acres.

During my childhood and indeed into the early seventies, the countryside was ever changing its patchwork design with equal variegation to announce the seasons. Back then, a glance at the countryside proclaimed the seasons, spoke of the greatness and possibilities of nature and made you so aware of its ability to just be itself in so many different and wonderful ways. This patchwork design was made all the more conspicuous by the large number of small fields and the diversity of crops that were constantly changing in both form and colour throughout the spring, summer and autumn months. Often, as I reflect on the themes of Seamus Heaney's or Gerard Manly Hopkins's nature poetry, I wonder what it evokes or conjures up for the modern reader in its very reverent enthusiasm for the activities of the seasons, given now that those activities no longer exist; or is it as these lines suggest 'the soil/Is bare now , nor can foot feel , being shod'.

Today, sadly, the changes are confined to merely the climate and hours of daylight. The countryside changes little throughout the year. Gone to a large extent is the habitat with its fauna and birds and to a certain extent its flora that so enriched one's life. The cuckoo, the corncrake and the skylark that gave voice to the life of spring and summer are rarely to be heard. All this and so much more that were wonderful parts of the fabric of life back then in the 1940's and 50's are no more. The organic crops and drills of vegetables that once sustained a healthy lifestyle are now replaced by imported foodstuffs in tins and plastic wrappings. Modern consumerism greets you even in the most remote of boreens as a continuous reminder of the price of progress. All that was worthwhile about the older way of life has been pushed aside to make way for the new, repeating once more the mistake made by so many of the other western countries.

Today mainly grazing and dairying across the country in contrast to tillage in the 40's & 50's

|

|

|

|

|

|

Field below the House Field below the House |

Big Meadow beyond the House Big Meadow beyond the House |

Field behind the house Field behind the house |

Field above the House Field above the House |

The High Meadow from the Hill |

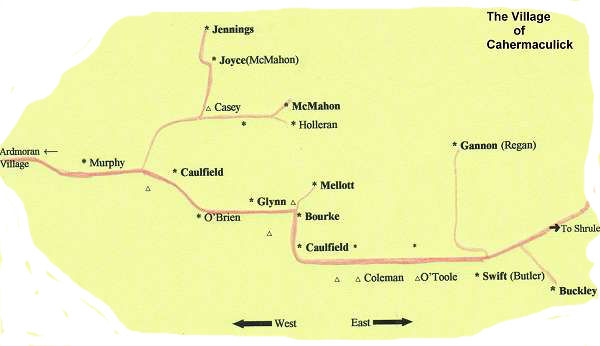

Cahermaculick did not exist as a village until the second decade of the twentieth century. Up until then it was part of the thousands of acres controlled by Lord Kilmaine* and his family. In the 1940's and 50's, the Townland of Cahermaculick had seventeen farming families whose names are shown in this diagram. All the families in bold print have died out except Joyce who has relocated to the Midlands and McMahon who has moved to the Joyce homestead. Regan and Butler through marriage have replaced Gannon and Swift. Most of those seventeen families were resettled there during the First World War from Turloughmore,The Neale and from around Ballinrobe. They were former tenants of lord Kilmaine whose family controlled thousands of acres of land in Co. Mayo alone. Most of this land including Cahermaculick was formerly used for grazing to provide stock for the English markets as was the case with other landlords whether absent or present. Most of the landlords used agents to conduct their business including the extraction of rent and labour from the tenants.

* Click here on The Neale for more information on Lord Kilmaine and the land situation.

Ireland has seen so much change in the last ten years as a member of the European Union - most of it I concede for the better - that it's difficult for the younger generation to perceive of an Ireland that was so very different from their own. To echo the words of W. B. Yeats, things "Are changed, changed utterly", but whether "A terrible beauty is born" remains to be seen. While conditions I suppose could only improve, no one could ever have expected or predicted such rapid change and improvements. I can think of few countries that have gone ahead in such leaps and bounds in such a relatively short period of time. This becomes all the more remarkable when seen within context of very keen competition from the big trading nations. Like other developed countries, Ireland will experience the ebb and flow of global trading. No matter what happens though, one thing is certain - Ireland will always be ready to take up the challenge. Gone forever are the many yokes of her past history, those yokes of servitude that fastened her to centuries of barbaric treatment and until quite recently to economic misery and stagnation.

Forward to Hard Times A (Cahermaculick Page 2)

Genealogy Menu

Hard Times

In the chapter on The Neale, we saw where the success of the Land League movement meant that the landlords were losing their power and grip on the land. Periodically though evictions continued to be carried out despite the protests and whole families, orphans and widows were forced into Workhouses like the one in Ballinrobe. These charnel-houses of the Great famine survived still to inflict utter pain and mental torture, separating families on entry and thereafter subjecting them to hard labour and often premature death.

Spurred on by the Land League movement, tenants were more than anxious to own their own land and in the spirit of Brehan Law, that for so long was part of their deeper memory, they insisted on that right. Land acts were passed providing for a degree of tenant land purchase. The Irish were at last emerging from centuries of coercion and oppression. Co-ops were set up that became the focal point of the community. Those changes as well as the founding of the GAA or Gaelic Athletic Association and the Gaelic League breathed new life into rural Ireland as up until the late 1890's the Irish were also barred on social grounds from competing in sports and games. The Gaelic League was founded to halt the decline of the Irish language and promote a revival of Irish culture. The literary revival that followed, based on a fast growing awareness of Irish nationality and inspired by Ireland's past, led to a Celtic renaissance that revitalised the Irish psyche.

The centuries of coercion, oppression and famine which had caused so much misery and pain had made poverty endemic and the cure proved ever so elusive. By 1903 when my father was born, life was improving, albeit ever so slowly, for the people of Mayo and elsewhere. By today's standards it was indeed a very exacting and meagre existence with few comforts. Homes were cold and draughty with no indoor plumbing and little furniture. Meals were cooked in pots and pans over open fires. Most farm work was done by hand with the aid of the spade and the fork, the sickle, the scythe and the rake. The donkey and the horse were the beasts of burden. When it came to farm work, the horse was the farmer's most prized possession as it was used to pull the plough, the harrow and the cart.

When my father’s family relocated to Cahermaculick from Turloughmore, the English had not done with Ireland yet. For a detailed account of more broken promises and the most shameful betrayal of the people of Ireland who must have felt that they were encountering the reincarnation of Cromwell in the atrocities of the infamous Black and Tans, refer to the pages of any history book on this period. Briefly, though, this is what occurred. In December 1918, at the General Election, all Nationalist Ireland declared its allegiance to the republican ideal, and the Sinn Fein policy of abstention from Westminister was adopted. In January 1919, the republican representatives assembled in Dublin and founded Dáil Eireann, the Irish Constituent Assembly, proclaiming the republic of Ireland once again as in 1916. A message was sent to the nations of the world requesting the recognition of the free Irish State, and a national government was erected.

No sooner had the new Government begun to function, established its Courts, appointed Consuls, started a stock-taking of the country's undeveloped natural resources, and put a hundred constructive schemes to work, than Britain stepped in, with her army of Soldiers and Constabulary, to counter the work, harassing and imprisoning the workers. This move of England's called forth a secretly built-up Irish Republican Army (developed from the Irish Volunteers), which, early in 1920, began a guerilla warfare, and quickly succeeded in clearing vast districts of the Constabulary who were ever England's right arm in Ireland.

Lloyd George met this not only by pouring into Ireland regiments of soldiers with tanks, armored cars, aeroplanes, and all the other terrorising paraphernalia that had been found useful in the European War, but also by organising and turning loose upon Ireland an irregular force of Britons, among the most vicious and bloodthirsty known to history - the force which quickly became notorious to the world under the title of the Black and Tans. And then, with carefully planned purpose to quickly break the Irish spirit and subdue the nation, was waged upon the Irish people - alike combatants and non-combatants, Irish women as well as men, toddling child and tottering aged - a war of vengeance, unparalleled for blind fury and fearful cruelty by any war in any civilised country of the world since the seventeenth century. The wholesale burning of a hundred villages, towns, cities, the looting, the spoliation of the inhabitants, though in themselves appalling, were as nothing compared with the cold-blooded murders perpetrated by the British, and the elaborate refinement of torture, worse far than death, which they visited on non-combatants as well as combatants.

It was intended that the job of "settling Ireland" should, like Cromwell's campaign on which it was modelled, be sharp, short, and decisive. It should be over and done with ere the outside world awoke to the fearful reality of what was happening. And the English press generally, the English correspondents of foreign newspapers, and the English cable service did their part to back the British army in the field. They saw to it that not only was the hideousness of their campaign in Ireland concealed from the world, but that instead the Irish fighting for freedom in a fearfully unequal fight were lied about and painted to the world as ruffians. And, loyally doing their bit in the disgraceful campaign of hoodwinking the world, the highest, most "Honourable" Government officials, from Prime Minister Lloyd George down to Irish Secretary, Sir Hamar Greenwood, from their places in the British House of Commons deliberately and persistently falsified the accounts of occurrences in Ireland, denied, without wincing, the barbarous crimes of the British which they knew and approved of.

Yet the well-planned campaign for the quick wasting of Ireland, and breaking of Ireland's spirit did not come off on schedule. The atrocities which were meant to frighten and subdue, only stimulated the outraged nation to more vigour: and by the time the fight was expected to end it was found to be only well begun. And, carefully as the army of falsifiers guarded every gate by which the truth might escape to the world, tricklings of truth had begun to find their way out, and the world was beginning to whisper of strange British doings in Ireland. More than by anything else, probably, the world was awakened to the truth of the situation in Ireland through the extraordinary heroism of Terence MacSwiney (Mayor of Cork in succession to the martyred MacCurtain), who in protest against the foreign tyranny which seized and jailed him, refused to eat in the British dungeon where he died with the wondering world watching on.

The general aspect of the British Campaign in Ireland is best summarised, perhaps, in the findings of the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland - a Commission whose members were selected by the American Committee of One Hundred - this latter being composed of many of the most representative men and women in America, Protestant, Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian and Jew - including Governors of States, Senators, Congressmen, Protestant, Catholic and Methodist Bishops, College Presidents, Editors, Business men, and lay men.

Here are the most remarkable of their findings:

"1. The Imperial British Government has created and introduced into Ireland a force of at

least 78,000 men, many of them youthful and inexperienced, and some of them convicts;

and has incited that force to unbridled violence.

"2. The Imperial British forces in Ireland have indiscriminately killed innocent men, women,

and children ; have discriminately assassinated persons suspected of being republicans;

have tortured and shot prisoners while in custody, adopting the subterfuges of `refusal

to halt' and `attempting to escape'; and have attributed to alleged `Sinn Fein extremists'

the British assassination of prominent Irish Republicans.

"3. House burning and wanton destruction of villages and cities by Imperial British forces

under Imperial British officers have been countenanced and ordered by officials of the

British Government, and elaborate provision by gasoline sprays and bombs has been made

in a number of instances for systematic incendiarism as part of a plan of terrorism.

"4. A campaign for the destruction of the means of existence of the Irish people has been

conducted by the burning of factories, creameries, crops, and farm implements, and the

shooting of farm animals. This campaign is carried on regardless of the political views of

their owners, and results in widespread and acute suffering among women and children.

"5. Acting under a series of proclamations issued by the competent military authorities of the

Imperial British forces hostages are carried by forces exposed to the fire of the Republican

Army; fines are levied upon towns and villages as punishment for alleged offenses of

dividuals; private property is destroyed in reprisal for acts with which the owners have no

connection; and the civilian population is subjected to an inquisition upon the theory that

individuals are in possession of information valuable to the military forces of Great Britain.

These acts of the Imperial British forces are contrary to the laws of peace or war among

more civilised nations."

All of this in the aftermath of the Great War, World War 1, 'the war to end all wars'. All of this in the fashion of a nation's conspiracy perpetrated in the most pernicious and criminal manner. Surely one of the lowest and most barbaric chapters in England's history. Surely one of the darkest hours in Ireland's history. .... And despite the number of Irish and of Irish descent in the dominion (commonwealth later) countries, these countries supported - and not often blindly - England's brutal and inhuman treatment of the Irish during my parents and grandparents' years of the first quarter and more of the twentieth century. The dominion countries' serious discrimination against the Irish is well documented. In fact when I settled in Australia in 1958, Prime Minister Menzies and his Foreign Affairs Department were still having some difficulty recognising the ambassadorial status of the Irish Diplomat appointed Ambassador to Australia, and chose instead to ignore his presence, despite the great contribution of the Irish in this country to its development and its role in the two world wars where to those soldiers Irish and of Irish descent went more than 60% of all Victoria Crosses awarded to our Australian soldiers.

The old adage and theme of many publications that 'good ultimately triumphs over evil' was more than put to its test in Ireland's case if you can conceivably see 'ultimately' as stretching over some three hundred and more years. Or was it the very nature of the evil itself that made it for so long so implacable?

In the spring of 1921 there was galloped through the English Parliament a "Home Rule Bill" for Ireland whose object was, by giving the eastern part of Ulster, the Orange corner, a Parliament of its own, to detach it from the rest of Ireland, thus dividing the nation on sectarian lines and thereby endowing the Irish nation with one of the meanest cuts of all, that has so festered her to this day.

Forward to Hard Times B (Cahermaculick Page 3)

Genealogy Menu

Hard Times

Despite Ireland's neutrality, the war years of 1939 to 1945 and the post-war period were times of extreme suffering and hardship, particularly for those in towns and cities, and much resourcefulness and ingenuity were required simply to eke out a basic standard of living and merely survive. There was a chronic scarcity and shortage of everything except for what the land could produce as most imports simply did not arrive because of the frequency with which ships were being sunk. A system of rationing known as 'The Emergency' was introduced. Each household received a ration book and could attend the local shop or the travelling shop once a week in order to receive its weekly ration of 2oz of sugar (57g), ½oz. of tea (14g) and three loaves of bread which were allowed per person if the family was in a position to pay for them. Often their allocated ration was not available or was insufficient forcing those who could afford it to buy on the "black market" where tea cost as much as £1 per lb. (.45kg). As each household sold eggs to the travelling shop, this provided a much needed boost to the family income as well as paying for the weekly ration. Some families were fortunate enough to receive clothing and food supplies, with items like tea and coffee, in the post from relatives in America.

During the long winter evenings, lighting was provided by paraffin oil lamps or by wax candles in the absence of paraffin oil. Central heating was a thing of the future but each room had an open fireplace where fires were lit when needed. The kitchen with its open fire was also the living room. Over the fire was fitted a steel crane that was adjustable and could be easily moved in and out over the fire. From it were suspended the cooking pots and the kettle. It was here at the table that we did our homework before the visitors arrived. For as long as I can remember, our home was the meeting place or communal centre of the nearby villages. During the long winter nights, the locals gathered there around the open fire to share stories, tell tales and spin yarns, play cards and conduct card drives as Christmas approached with turkeys and geese as prizes. Apart from the occasional radio program, local community play, parish dance, wedding or wake, our entertainment was home made. There is, however, one occasion that really stands out in my mind. Mick Caulfield who lived on the farm next to ours held all those present captive for all of two nights with a fantastic story that he began about nine o'clock one evening, retiring at midnight only to continue the story about the same time next evening for just about as long again. And as my father used to say, "That's no word of a lie".

Landowners were obliged under another measure introduced called ‘Compulsory Tillage' to till a certain proportion of their land in order to provide home produced goods to cater for the population. The harvesting of wheat, oats and barley was part of this arrangement and farmers kept so many bags of oats and wheat for their own use. In our case, these were taken as needed to the nearest mill or crusher in Shrule or elsewhere. The flour which was merely crushed wheat was made into wholemeal bread called caiscín (Kawshkeen). We all loved this type of bread with a generous spread of homemade butter.

A number of farmers, particularly those with large families, grew sugar beet which in our case was sold to the sugar factory in Tuam. Depending on the amount grown, and this was measured and checked by inspectors from the sugar factory, farmers were rewarded with so many stone of white and brown sugar. Some of this would go to needy or worthy neighbours who had helped the family in other ways with, for example, knitted socks and jumpers or other garments which were greatly appreciated as only an inferior grade of cloth was available.

As new shoes were difficult to obtain, people became excellent cobblers. I can recall the fine job my father did in repairing our old shoes with new half soles and heels. This he did by placing them on the iron shoe last and attaching the new leather with studs or tacks to original soles before shaping them to size with his special knife. More often than not though he sewed the new half-sole to the original using an awl and hemp thread treated with wax to make it waterproof. Clogs became increasingly popular and didn't I hate them. One incident in particular stands out in my mind. I was about eight at the time and we were on our way home from primary school. There was a lot of fresh snow on the ground and with every step I took in my clogs higher and higher I went, often falling over, with clump after clump of snow attaching itself with a vengeance to the steel tipped wooden soles of my clogs. It was ever so hard to remove the snow, and it happened again and again all the way home. Despite the help of my older brother, John Joe, I became ever so frustrated and upset that not even John Joe has forgotten the incident.

Of course the bicycle was the primary form of transport but like just about everything else bicycle tyres and tubes were ever so scarce. As children we spent many exciting hours constructing our own bikes from those parts occasionally discarded by others in the neighbourhood. There was nothing we couldn't do with those parts. What wouldn't fit was made to fit by patient and loving modification. Old tyres and tubes when available we in time mended with expert ease. Wooden blocks were often used when standard pedals were unavailable. To fit the blocks to the spindles, we burnt out the holes in the blocks with a narrow piece of steel heated in an open turf fire. Old saddles were mended and chains adjusted to fit, and though brakes and mudguards rarely came into the equation the final product was road tested with the anticipation and pride associated with a modern day lamborghini.

Understandably, some tasks were considerably more appealing than others. On my way to and from school, I enjoyed watching the crops grow and the meadows, which were havens for local fauna and such birds as the skylark, sway to the movements of the wind. There was something special about the smell of newly cut hay explaining perhaps why I liked helping out at harvest time. Nothing could beat working in the bog and spreading the turf, and anyone I have ever spoken to always agrees. As children we looked forward to working with Dad in the bog which was located at Dalgan just a few miles east of Shrule and each household had its own plot there. Those were really great times during the long summer days, and nothing can compare to the feel of walking barefooted on the bare bog with the squelched fresh peat rushing between your toes, or enjoying the picnic-like atmosphere while sipping the sweet bog tea prepared over the bog fire in that special bog can, or racing across the bog jumping over the new cuttings and channels to visit our neighbours, cuttings often ten feet deep filled with that brown bog water but rarely an obstacle to the vigour of youth knowing that to fall prostrate was a sort of comfort in itself. Observing the precision with which Dad used the sleán (shlaun - a special turf spade) to cut and toss the sods of turf up for us to spread and our handling those fresh and soft and slippery sods - real kids' stuff - are among those pleasant memories never to be forgotten.

Seeing nature quietly at work in the fields was something else. After they were ploughed and harrowed, and the seed broadcast by Dad and rolled into the soil, the fields in contrast to those other fields around lay flat, brown and bare. Brown and bare also were the fields of drills from end to end that were potato, sugar beet and mangel seeded. But to witness the transformation to shortly follow was such a wonderful experience. Over night the fields changed their appearance completely to a lush green, with the drills all displaying straight long green lines along the top. That was indeed a sight to behold next morning, and in no time at all the young plants ever so profuse were about 100mm high. Whenever I hear the expression 'hard labour', I can picture myself on my knees astride drill after drill of sugar beet or mangels, for hours on end, performing the thinnowing process as I moved slowly along each drill, leaving one plant standing about every 170mm and removing bare-handed all the others. Imagine those skinned and calloused knees and hands at the finish or 'láimhiragh' as Mam used to say! Seamus Heaney's poem "AT A POTATO DIGGING" though disturbingly evocative of the Great Famine does describe the task of potato picking well. The words "Fingers go dead in the cold" bring back many memories. We all dreaded the job of picking the potatoes in late autumn. It was the most back-breaking, boring and tiring job imaginable with, to echo the words of the poet, 'heads bowed and trunks bent and hands fumbling towards the cold earth' or dragging full buckets to the pit.

A few of the tasks that fell to us as children were in hindsight downright dangerous. If you have ever seen or used a hay fork with its two very long and pointed prongs, you'll appreciate the dangers in spreading and compacting hay on top of the cock or stack as it was forked up to you by often more than one person. It was rare to come away without a few pricks in your shins and thighs for your troubles.

I often wonder where Mam found the time for all the work she did. As well as often helping in the fields, she looked after the poultry, baked bread, cooked food for a large family, prepared the churn and made butter, cured bacon, carried water, did the washing, cleaned the house, prepared the 'shlits' (pieces cut from potatoes for seed) for planting, did the milking, made and mended clothes and helped with homework and more.

There were always lots of animals around and many pets among them, but there was one in particular that was everyone's favourite. Her name was Winnie and she was much more than one of our farm horses. She was a wonderfully kind and caring friend to us all. We grew up with her and from a young age could handle and work with her as well as any adult. It is difficult to imagine how such a big, sturdy animal could be so co-operative and dare I say discerning. She was happy to do whatever we asked her as long as it was safe and didn't present a threat to us as children. With bridle in hand we would call out to her and she would respond immediately. Recognising our size, she would lower her head to allow us to put the bridle on correctly. She would move alongside the stone wall to enable us to get onto her back. If she felt you weren't balanced properly or about to slip off she stopped immediately in order to allow you to re-balance. She would canter or gallop only when she sensed you were old enough to manage it. I often felt that she must have had eyes in the back of her head whenever she was harnessed to the cart. To sit high on top of a cart load of hay or sheaves was exciting, but the moment we tried to stand up Winnie stopped immediately and refused to move till we were seated again. The simple way to get into the cart was to step on the spoke of the cart wheel and hop aboard. There was no way you could get her to move if you were anywhere near the wheels or in front of the cart, and she would look from side to side to see where you were. I can recall so many situations when she intervened in order to ensure our safety. One in particular stands out in my mind. I was fetching a canful of fresh water from Caulfield's well and had just crossed over the style into our property. As I crossed the field where the sheep were grazing, I noticed Winnie who was in the same field galloping towards me. Little did I realise at the time that a young ram had positioned himself to charge at full pelt. Suddenly Winnie had positioned herself between the ram and me challenging every one of his moves while at the same time half turning her head towards me and neighing with such urgency as if saying, "Get to hell out of here quickly". And of course I gratefully obeyed.

In the weeks leading up to Easter, we would leave our warm beds at seven in the morning and cross the fields to check on the number of new-born lambs. The fact that it was often freezing cold escaped our attention as our minds were preoccupied. Occasionally, when we came across a sheep having difficulty lambing, we would give her whatever help she needed in order to ensure the safe birth of her lamb. Sometimes that meant using techniques that we had acquired along the way, and sometimes it meant summoning our father to the rescue when the going got too tough. To be given an egg for breakfast was a rarity and came as a reward for having achieved something. Arising early in the cold of the spring morning to locate the new-born lambs was deemed such an achievement. During the coldest winters we were clad in shorts, shirt, and jumper which was usually home made. Boys had to wait until they had finished primary school to qualify for the wearing of trousers. It wasn't so much a case of having or not having. It was instead a case of making do with what you had. No one that you knew had very much more or less than yourself. Being a child or teenager didn't set you apart from your parents and other adults. Generally speaking, you were involved in their conversations and adults accorded you the same respect as they showed one another.

The local smithy was always in great demand, and of course we all could recite "The Village Blacksmith" from an early age. There were a few blacksmiths in our area but the one I saw as our blacksmith was Jack Ford of Kill (Cille) whose forge was there at the junction of the Shrule and Cahermaculick roads. His trade was a busy one and was in great demand until the early 1950's when the tractor gradually took over. It was common to see a number of horses in line to be shod just about every day but particularly during spring-time. I can't recall ever going past there without stopping to watch him ply his trade. Like so many others, I found the whole culture of the forge fascinating from the rhythmic ring of the anvil heard from afar and the lingering cloud of smoke with its rather intoxicating smells to the roar of the bellows and the sight of white heat as the irons turned white from the great heat of the forge fire.

The making and fitting of steel tyres on large wooden wheels for carts, traps and side cars was a very difficult job that required great skill and patience. To observe the welding process alone of knotting the ends and heating them to the point of melting before forcefully hammering them to create the perfect weld was quite an education. Among other things, the farmer also relied on the blacksmith to supply and repair steel shoes for both the standard and drilling ploughs, and leaves and springs for the harrows, as well as cart axles and gates, both plain and fancy.

That was the Ireland I knew and that was the Ireland I left in 1955. As I have said earlier, Ireland has seen so much change in recent years as a member of the European Union, and most of it for the better, that it's difficult for the younger generation to perceive of an Ireland that was so very different from their own. Despite the deep scars still in the Irish psyche, gone forever are the many yokes of her past history, those yokes of servitude that fastened her to centuries of barbaric treatment and until quite recently to economic misery and stagnation. Ireland today 2007 is a very modern and vibrant nation with an unique culture and a very successful economy, and with that same indomitable spirit and sense of fun and optimism that have been the hallmarks of her dignity down the centuries and hopefully into the future.

My parents have passed on but I am grateful that they lived long enough to see the new Ireland. The land that became my grandparents' land nearly a hundred years ago is still in the family. Today it is worked by my brother Noel and his family.

Nonnie, Pat, Martin John Joe, Bridie & John 1974 |

Cahermaculick Family Home 1960's |

Paula Hogan ex Sydney with Mum, Dad, Noel & Tim 1976 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Coleman Home in Cahermaculick as it was until 1974 when a new one was built

in the field across the road

Clan Coleman

Clan Coleman

Harvested Wheat in stooks

Harvested Wheat in stooks Martin & Michael - Tim & Speed 1974

Martin & Michael - Tim & Speed 1974 Haystacking in the haggard

Haystacking in the haggard  Taking oats to the haggard

Taking oats to the haggard Drills of potatoes

Drills of potatoes